Consider the following problem: we have a 2x2 grid with 4 cells, each of which we can paint black or white. Two paintings are considered identical if they can be rotated to look the same. How many distinct paintings are there?

Before we apply Burnside’s Lemma to this problem, let’s formalize the lemma’s general conditions. The lemma requires a group of actions which act on a finite set . In our case, consists of rotation by 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°, and consists of all possible paintings, not necessarily rotationally distinct.

Note that the term group has a very specific meaning in a math context. Importantly, if denotes the action derived by first performing , then , then a group must satisfy the following four conditions:

- If two actions are in , must be in as well.

- There must be an identity element .

- Each element must have an inverse element such that

- must be associative; that is, =

For instance, if we removed 270° = 180° + 90° from , would no longer be a group.

You can see this is basically a generalization on the traditional notions of multiplication and division, although it does drop the commutative property.

With that out of the way, let’s return to our original problem. In group theory terms, our problem is equivalent to finding the number of orbits of when acted upon by , denoted .

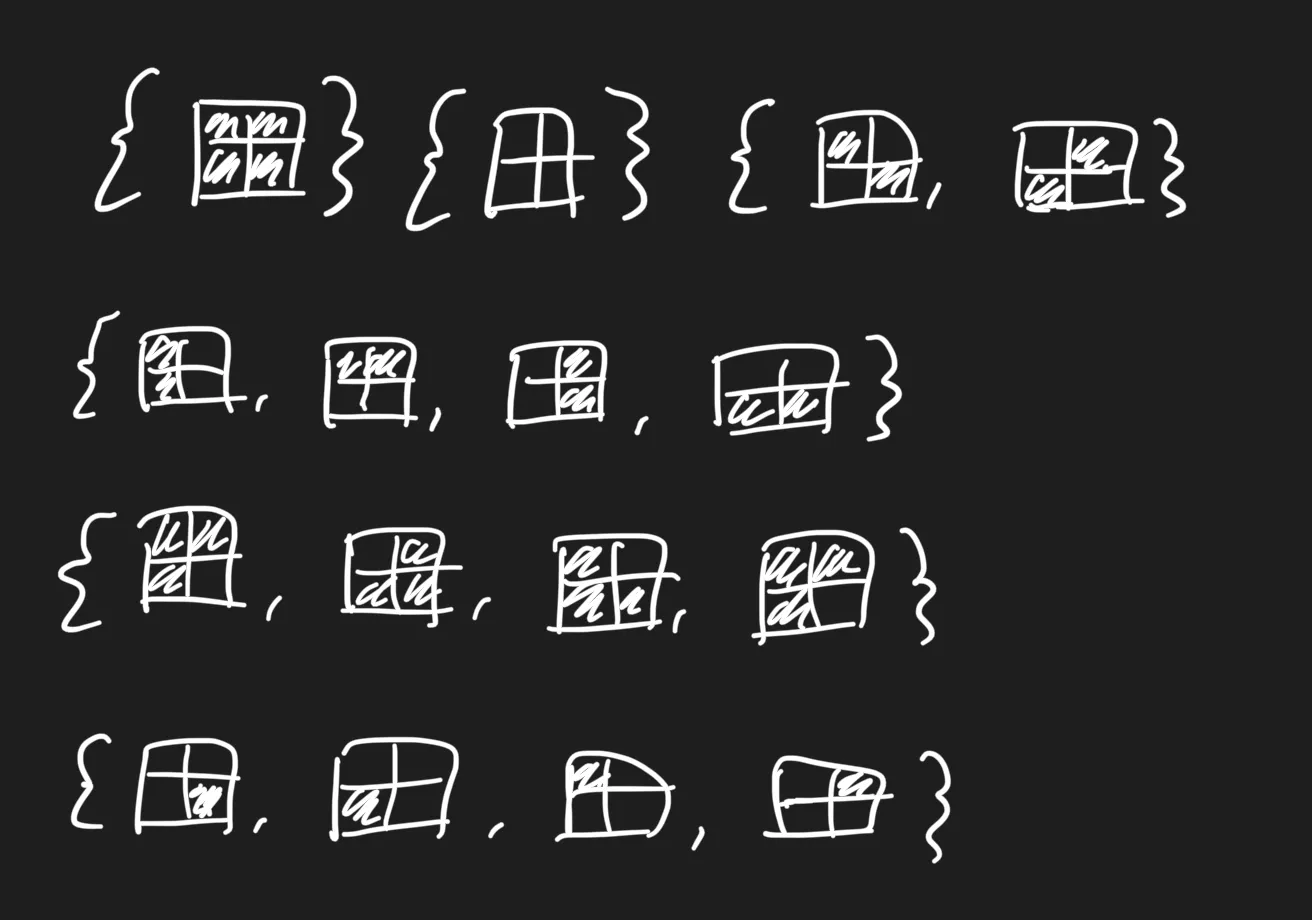

The six orbits for our problem. This set of sets is , and its size is the number of orbits.

The six orbits for our problem. This set of sets is , and its size is the number of orbits.

Note that within each orbit, all elements are rotationally identical. Since each of these orbits contributes 1 to our final answer, it makes sense to consider dividing each orbit’s contribution evenly across its members, in which case each member should have an individual contribution .

Formally, let denote the orbit to which painting belongs.

As the notation suggests, is exactly equivalent to the set obtained by applying every action in to . Make sure you understand why!

Then, we can write the following:

Cool, but how does this help?

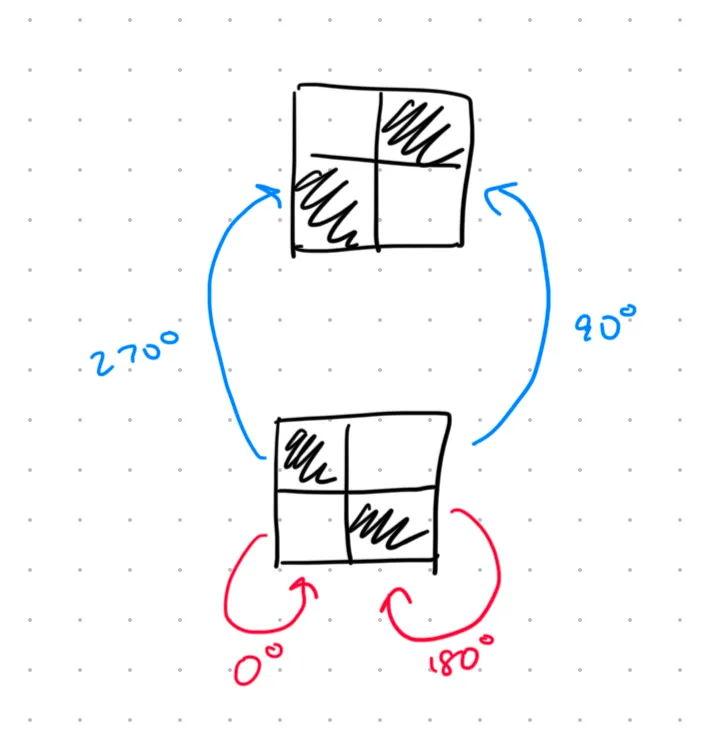

Let’s visualize the action of like so:

If we construct such graphs for other possible states and transformations, we notice an interesting property: for every possible initial state , every final state will have the same number of edges going into it. For instance, in the image above, with the initial state being the bottom grid, every final state has exactly 2 edges going into it. Let’s denote this number of edges as .

If we construct such graphs for other possible states and transformations, we notice an interesting property: for every possible initial state , every final state will have the same number of edges going into it. For instance, in the image above, with the initial state being the bottom grid, every final state has exactly 2 edges going into it. Let’s denote this number of edges as .

I hope the fact that each state has the same number of in-edges feels intuitive to you, and as such, I will not provide a proof here. If you are stuck, the most important property to remember here is the closure property of and/or the fact that every element in has an inverse element.

This means that the total number of actions, , can be written as .

Now we just need to know the best way to determine . Since the number of incoming edges to all final states is the same, the most intuitive choice for the final state to consider is itself. Thus, we can define simply as the set of operations which leave unchanged, more commonly referred to as the stabilizer of , and it then follows that . We now arrive at the following important result, the orbit-stabilizer theorem:

This means we can rewrite our above summation like so:

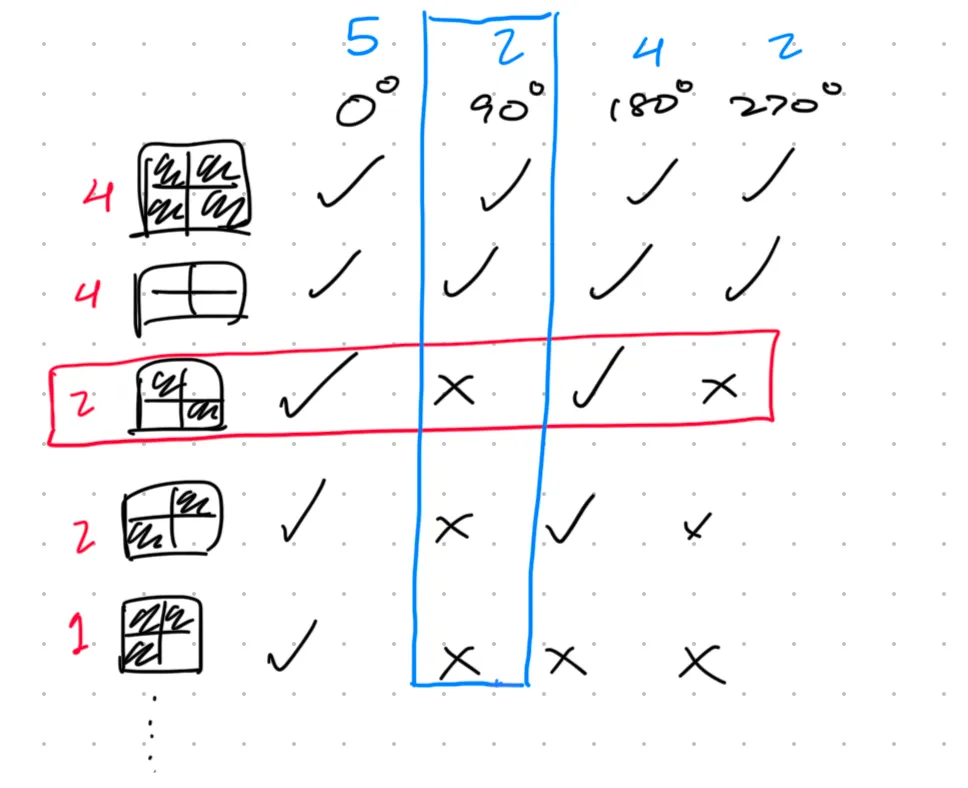

To get Burnside’s lemma, we need to apply one more trick to evaluate . Consider the following diagram:

A check/cross in a given position indicates whether each operation is a stabilizer of each state. Our current summation sums the red numbers (along the rows) which are derived by counting the number of check marks in each row, but a standard combinatorial trick is to try summing the blue numbers (along the columns) instead. Observe that the blue number corresponding to each operation is precisely the number of elements for which , also referred to as the number of fixed points of , .

A check/cross in a given position indicates whether each operation is a stabilizer of each state. Our current summation sums the red numbers (along the rows) which are derived by counting the number of check marks in each row, but a standard combinatorial trick is to try summing the blue numbers (along the columns) instead. Observe that the blue number corresponding to each operation is precisely the number of elements for which , also referred to as the number of fixed points of , .

This trick is more commonly referred to as swapping the order of summation as we can rewrite the visual approach presented above like so:

Putting it all together, we finally arrive at Burnside’s lemma:

I hope this article demystified the lemma for you, and please feel free to open an issue on GitHub if you have any further questions!